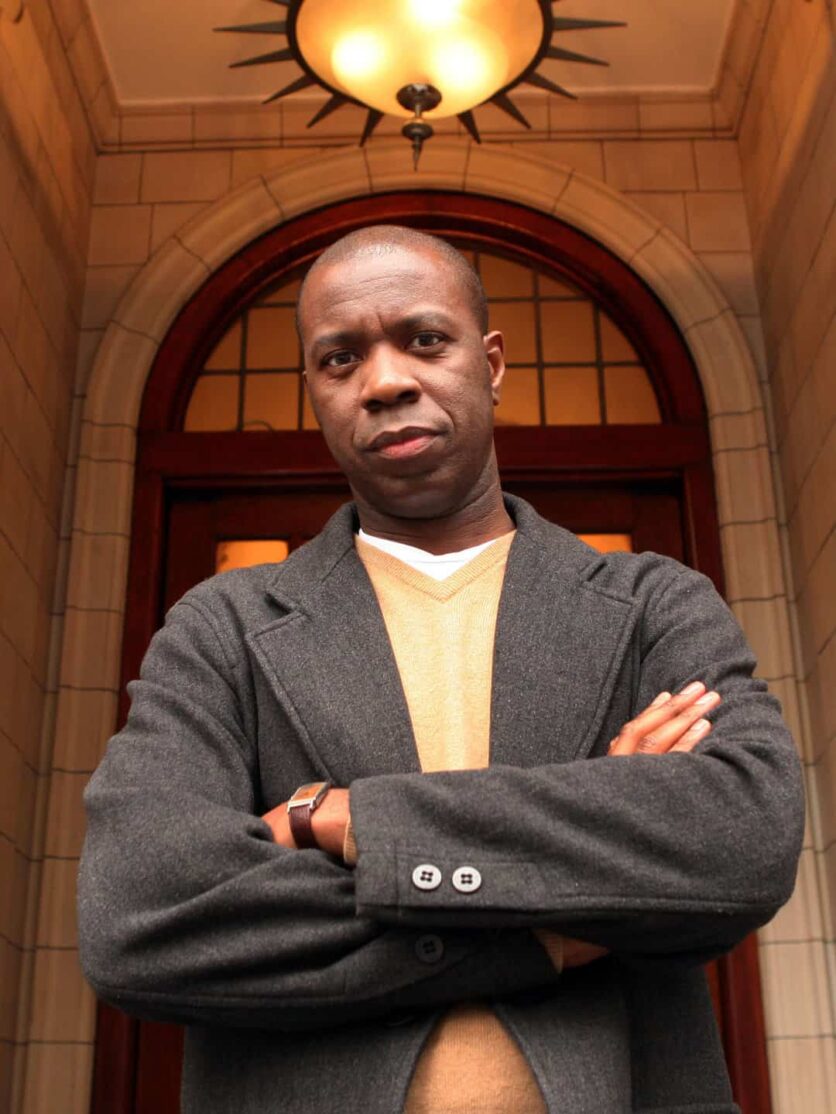

“It’s supposed to be intimidating. That’s the whole point!” Clive Myrie could easily be talking about reporting from war zones. He’s been doing it for a quarter of a century, covering conflicts from Liberia to East Timor to Ukraine. But the veteran, Bolton-born newsreader and BBC World Affairs Correspondent has, for the last year, been placing himself at the fulcrum of an entirely different scenario based around fear and darkness where a lack of knowledge can result in brutal elimination.

“Mastermind is definitely scary. But there’s always that sense when you’re watching that you want to know how you’ll do yourself. It’s a way of finding out not just how little you know, but also how much you know. I like the idea of families joining in and trying to answer the questions.”

It was exactly half a century ago this autumn that the first episode of Mastermind aired. Hosted by the late Magnus Magnusson, the show’s distinctive, and uniquely intimidating format, was inspired by the Gestapo techniques used on the programme’s creator Bill Wright, who spent three years as a prisoner of war during World War Two. The format, 50 years on, is almost identical.

And Myrie, 58, is happy to admit that there are no plans to ‘soften’ the show’s brutal format that sees contestants walking, often with physically noticeable trepidation, to the famous black leather chair to answer quick-fire questions on general knowledge and their own specialist subject matter.

“Let’s be straight, it is an interrogation. You’re being grilled, as the clock ticks down, on what you know,” says Myrie. “That can be as spine-tingling and uplifting as it is frightening.”

Taking over from John Humphrys as interrogator last year only cemented Myrie’s position as one of the BBC’s most valuable assets. Away from the relative comfort of the Mastermind studio, Myrie has, of course, become one of television’s most well-known, and decorated, war reporters, flying in to some of the roughest corners of a world where the rules of engagement are shifting in an ever more dangerous direction.

“Just a couple of weeks ago I had to do a refresher of a Hostile Environment course which war correspondents do,” he says. “Basically, it teaches you how to work effectively and safely in war zones. You learn about flak jackets and what different kinds of mortars and shells can do to people. The biggest change from 20 to 30 years ago is that journalists are now the targets. We are seen not just as impartial observers trying to report the truth of a war. We’re seen as participants by one side or the other in the propaganda. By reporting the war fairly, you can immediately be seen as the enemy by one side.”

Anyone looking through Myrie’s Twitter feed for an insight into his personal views on the conflicts he covers will be disappointed. When pushed, however, he admits to feeling an acute sense of distress at what he’s seen over the past nine months of reporting from Ukraine.

“It’s a particularly nasty and brutal war with two major European armies,” Myrie asserts. “You walk around any bombed-out area on the outskirts of Kiev, or a city centre or residential area that’s been heavily hit, and you see the devastation. I just imagine in my own mind the hell-scape that’s been visited on people cowering in their basements and their sheds. Seeing all that is just dreadful but the column of burnt out Russian military vehicles in Bucha really stuck with me. There were bodies of charred Russian soldiers still inside the tanks.

“[Journalists] are seen not just as impartial observers trying to report the truth of a war. We’re seen as participants by one side or the other in the propaganda.”

Clive Myrie

“But it’s always the attacks on the defenceless that stick with me the most. It’s the attacks on residential areas where there are no soldiers, no military installations at all. These are areas that are simply attacked to sow panic and fear and put pressure on the authorities to change their war posture.”

In front of the camera, Myrie is the consummate diplomat, reporting on the most emotive of stories with unwavering composure. Any “pushing” he does behind closed doors at the BBC is, he tells me, directed at getting permission to cover stories in parts of the world where conflicts fly under the radar of much of the British print and broadcast media.

“There are stories going on all over the place that aren’t getting the attention and oxygen that perhaps they should,” says Myrie. “The BBC can’t cover everything – although it does try its very best through the World Service. The civil conflict in Ethiopia right now is something that I’m getting a lot of comments about online but is only really getting featured in the middle of some newspapers every now and then. Then there’s the situation in Yemen and the attacks in East Africa and the problems with Islamic militancy in the Sahel region in southern Sahara. I’m keeping a close eye on Taiwan, too, and the situation there with the tensions with China.”

Myrie was born in Lancashire to Jamaican parents. Since he first began as a radio broadcaster for Independent Radio News, reporting from Belfast in the early 1990s, the media landscape has changed beyond recognition. Yet, despite now being one of the BBC’s most recognisable faces, Myrie believes a lack of diversity in the media is still a pressing issue.

“It’s certainly not a case of ‘job done’. Representation is getting better but we have to will the change. You have to have a public shopfront representing diversity for certain. It was Sir Trevor McDonald who was my great influence as he was pretty much the only person on TV when I was growing up who looked like me.”

Living in London with his partner of 30 years, Catherine, who works as a furniture restorer and upholsterer, Myrie’s frenetically busy schedule only has the briefest of respites, usually in the form of a holiday to Italy where he can indulge in his love of classical music. The BBC’s recent Ukraine’s Musical Freedom Fighters with Clive Myrie delved into that passion, following Myrie as he travelled across Ukraine to meet musicians who were preparing to leave their families in order to create an orchestra and perform at the Royal Albert Hall.

It was a rare insight into Myrie’s personality away from the camera, yet when I ask if he might one day use his limited spare time to write something even more personal, about his life and his opinions, his response is self-effacing.

“For me to have a space to give my own opinions would go against everything the BBC has stood for over the past century and so it just isn’t something that interests me. It’s just not part of my make up to just dribble on about what I think about something. You’re never going to confuse me with Owen Jones or Peter Hitchens, that’s a promise!

“I have thoughts on Liz Truss, Keir Starmer and Boris Johnson. I’m a human being and I have a vote just like everybody else in Britain. The difference is, when I walk through the doors of Broadcasting House my thoughts suddenly, miraculously, majestically disappear! That is the point. People are not paying the licence fee to hear my opinion. They’re paying it to hear factual accounts of the news and my efforts to dig as deep as I can within me to find the truth.”

And yet, even Myrie, clearly so deeply committed and impassioned by the mantra of giving us the news ‘straight’, can’t help but feel occasionally peeved by the verbal crutches other journalists use when deploying the nightly news.

“I do get irritated a little when I hear journalists and news reporters on TV responding to a question with the word ‘absolutely’,” he laughs. “I promise you that now I’ve said that, you’ll notice it all the time. It’s not the worst thing in the world but it does make me want to suggest that there are other words out there that can be used other than ‘absolutely’.”

With a schedule full to bursting with news reading and now, interrogating the British public on one of TV’s most popular quiz formats, it seems to be the quest for veracity in whatever Myrie does that lies at his core. That, coupled with the desire to hear the stories of individuals who, through no choice of their own, have been placed in the centre of war, are what propels Myrie into getting on yet another flight to a difficult corner of the world.

“Civilians are always bearing the brunt of armed conflict. But I’ve seen more and more cases of civilians being specifically targeted in recent years. It’s changed, it’s gotten worse,” he says.

“It’s made me even more determined to try and tell the truth and try to be as objective as possible. It’s stiffened my resolve to report on the mechanics of conflict and the dynamics of the wars we’re living through.”

Ukraine’s Musical Freedom Fighters with Clive Myrie is available on BBC iPlayer now

Read more: How Lady Chatterley’s Lover kick-started the Swinging Sixties

The post Clive Myrie on reporting in Ukraine and his hope for media diversity appeared first on Luxury London.