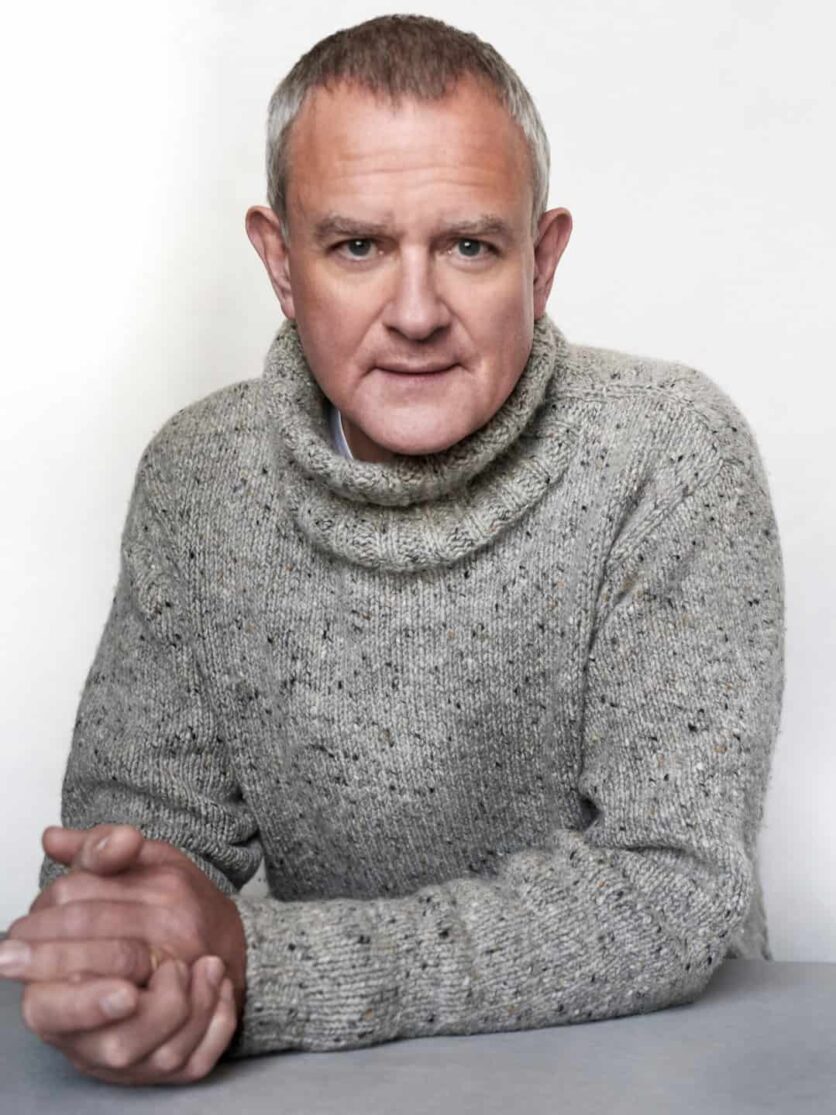

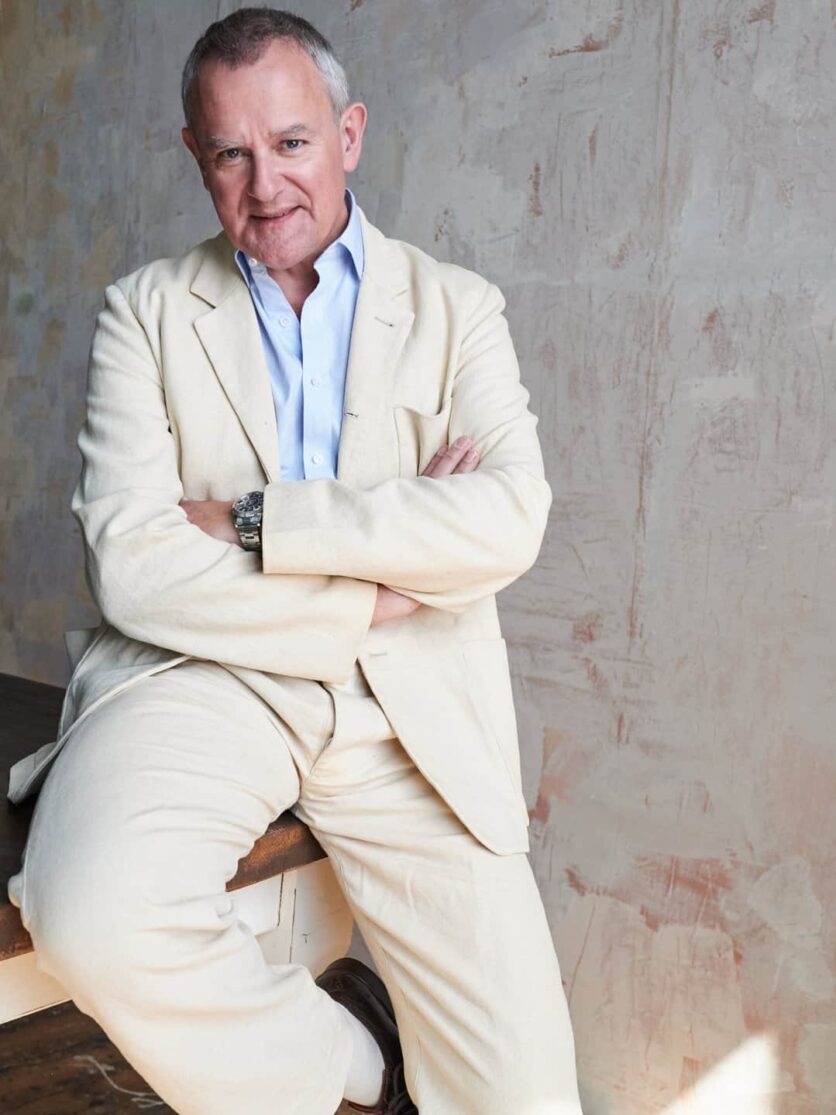

‘OK,’ says Hugh Bonneville, leaning across a New York restaurant dinner table, in a scene I’ve nabbed from his entertaining new memoir, Playing Under the Piano, for the purpose of starting this interview with a quasi-dramatic, big-money Hollywood anecdote. Our actual interview, arranged to promote said memoir, and Bonneville’s latest gig – the BBC’s Brink’s-Mat-inspired miniseries The Gold – took place in a restaurant in Soho. But every interview you’ve ever read starts with the interviewer saying they’re sat in a restaurant in Soho. And then by describing what the interviewee is wearing. (Kettner’s, if you really must know. Hugh’s choice, not mine. A good choice. Less clichéd than Soho House, my suggestion. And a green, three-piece tweed suit. Very English-country-gent-up-to-the-Big-Smoke-for-the-day. Very Hugh Bonneville.) Back to the scene…

‘How much does the film have to gross on its opening weekend,’ says Bonneville, ‘for Allen and I to get the chopper to Santa Barbara next weekend?’

The journey, it is explained, will take around two hours by car, more with traffic. The chopper can do the distance in a skip. Bonneville has never ridden a chopper. And the usually-reserved, unfailingly-polite, Cambridge-educated, typically those-who-ask-don’t-get Brit is feeling uncharacteristically un-British.

‘Hmmm,’ muses Peter Kujawski, Chairman of Focus Features, financier and US distributor of the film in question. Kujawski thinks for a moment. He likes the movie. But he’s also acutely aware that he’s taken a punt in fronting the money for the thing.

‘$25 million,’ he says, confident he won’t be putting his hand in his pocket to indulge the mad helicopter fantasies of the tipsy, red-cheeked Englishman.

That weekend, 20-22 September 2019, Downton Abbey, the first of the two films spawned (thus far) by the ITV smash-hit period drama, makes $31 million at the US box office. It goes on to become Focus Features’ biggest-ever domestic hit, grossing more than $96 million in the States and $194 million worldwide. Kujawski is good to his word. The chopper from the Van Nuys airfield to Santa Barbara takes 25 minutes. On the way back, as the helicopter charts a course along the Californian coast, Bonneville looks down at the chumps stuck in traffic on the Pacific Coast Highway. ‘Schmucks,’ he doesn’t think, because this is Hugh Bonneville, and Hugh Bonneville would never indulge in such smug, highfalutin thoughts. Even if he is drinking Whispering Angel.

‘Taking off in that helicopter and drinking overpriced rosé at someone else’s expense was the most unashamedly glitzy Hollywood moment of my life,’ he writes. A mountain-top moment in a life that, by Bonneville’s own admission, has had plenty more ups than downs.

Hugh Richard Bonniwell Williams was born in Paddington, ironically, in 1963. His father was a Cambridge-educated urological surgeon; his mother trained as a nurse before joining MI6 on the sly. “I had no idea for 30 years.” After clocking mum in the hospital canteen, Dad had asked her to the annual dance. They were married for 64 years, before a respiratory infection took her “in less than a day” in 2015 (Hugh’s brother, Nigel, died suddenly two years later. His Dad’s twin brother passed away not long after that).

When Hugh was six the family relocated from East Sheen to Blackheath. Dulwich College Preparatory paved the way to Dorset’s Sherborne School for boys. Culture was always there, in the background. Museums. Exhibitions. Art galleries. “A low-level exposure to the arts, not that I really realised.” Out of everything, it was theatre that really hit the mark. Seeing Peter Cook and Dudley Moore on stage are fond early memories. “The power of comedy, you know. Wow, just wow.”

He studied theology at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, thinking he’d maybe become a lawyer. He wound up at the Webber Douglas Academy of Dramatic Art, then the National Youth Theatre. Bonneville’s first pro gig involved bashing a cymbal in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. That was at Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in 1986. “I was understudying Ralph Fiennes as Lysander.” Fine place to start. Bonneville, by his own reckoning, hasn’t stopped since.

Roger Spottiswoode, Tim Fywell, John Hay, Kenneth Branagh and George Clooney are among the directors with whom Bonneville has worked – though it is Howard Davies and Roger Michell that he speaks of most fondly. He’s starred alongside Julia Roberts and Hugh Grant, Matt Damon and Bill Murray. Plus, fleetingly, Pierce Brosnan and Michelle Yeoh. Then, for the past decade, of course, Dame Maggie Smith. “Ten years of getting to call her ‘mum’. Brilliant, just brilliant.”

Hugh Bonneville is one of the luckiest actors Hugh Bonneville knows. Theatre, radio, television, film. The work hasn’t stopped coming. The secret? ‘Beyond turning up on time and not punching the director if you can possibly help it, I have no great tips of the trade to impart,’ he writes in the book.

There have been notable gear changes. Shifts in acceleration. Doors that opened doors that opened doors. Tomorrow Never Dies taught him that actors are commodities. Livestock and meat. Success equals currency, no matter how small the part. Bonneville had just a single line in James Bond’s 1997 outing. But that single line led to eight lines in 1999’s Notting Hill. Five years previously, Bonneville had narrowly missed out on Four Weddings and a Funeral. Notting Hill felt like recompense. “It’s nothing to do with your talent, really, more about your perceived market worth.”

Downton Abbey. Fifth gear. Six seasons. A torrent of awards. A Golden Globe and two Emmy nominations for our man Hugh. Three Screen Actors Guild awards for the cast. A special BAFTA in recognition of the unique contribution the series made to UK television. “Without Downton, I don’t think I would have met a small bear from Peru. Or have worked with George Clooney. Or have been invited to the White House.”

The bear. Bonneville wasn’t sure. ‘Giving Michael Bond’s beloved character the Hollywood treatment had disaster written all over it,’ he wrote. The first Paddington (2014) grossed more than £220 million worldwide and earned two BAFTA nominations, including Best Film. Paddington 2 (2017) made another £180 million. Three BAFTA nominations, also Best Film.

‘Michael Bond [author of the original books] appeared in the first Paddington film, sitting outside a café, raising a glass of wine to his creation as the bear first took in the sights of London. He died on the last day of filming for Paddington 2, aged 91.’

The book, a “‘memoir’ because ‘autobiography’ seems to have a claim of factual accuracy about it”, is good. So good that Bonneville has lost count of the number of times someone has asked whether he actually wrote it. Apologies, no offense. “None taken.” He’d stabbed at screenplays before, none of which ever quite got off the ground, but nothing properly long-form. It was his son, Felix, a university student who last year knuckled down to his own bit of writing, that shamed him into it. After that, Bonneville managed his first draft in less than three months. Show off.

“The working subtitle was Highclere to Hollywood, but my son said ‘No, it should be From Downton to Darkest Peru’. Those were obviously the two projects that most landed with him. And others, I expect.” The main title, Playing Under the Piano, is a nod to a memory from nursery school. Bonneville would hide from the rest of the class, playing by, not with, himself under a piano.

The book is funny: ‘Sometimes you read of actors going into the audition room and smashing up the furniture and impressing the director so comprehensively with their I Don’t Give a Shitness that they instantly get the part. Other times the police turn up. Tricky to know how to pitch it.’

It’s touching. On his father, who the family is slowly losing to dementia: ‘It’s as if he’s in a glider, high up there, silently, elegantly, effortlessly circling, peeking out of cottonwool clouds for a moment before disappearing out of view. Calm, content, I like to think.’

It’s poetic. On Carry On actor Bernard Bresslaw: ‘His deep baritone voice had a timbre that sounded as if it had been created by mooing into an empty wooden cask of madeira, warm and rounded but with an intrinsic echo of melancholy.’

And, on the 2012 Olympics, which provided Bonneville with one of his meatiest and most-loved roles to date, Head of Deliverance of the Olympic Deliverance Commission in the highly-acclaimed mockumentary Twenty Twelve, it is, as elsewhere, introspective. On himself, and on us:

‘As the Games approached, the Great British national sport of Cynicism limbered up in the pubs and in the press, ready to express its flabby, sneering, lazy self in action. The Games were going to be a disaster, Britain couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery, or if it could it would be a brewery like the Millennium Dome that had promised to blow our minds and in the event was Quite Interesting.’

The book is non-political. Bonneville is not apolitical. A Deputy Lieutenant of the County of West Sussex since 2019 (an unpaid public service role), he tweets, or re-tweets, regularly. About US politics. About Ukraine. About Gary Lineker. “Social media, hmm, yes, we all have good things and bad things to say about social media, don’t we? When one does put their head above the parapet, the number of times I get ‘Shut up, sit down. You’re just an actor’.” All Bonneville can say to that is, “Thank God for President Zelenskyy – because he’s ‘just an actor’ and now he’s probably the most inspiring national leader since Churchill.”

I can see it. The Rt Hon Hugh Bonneville MP. Bonneville can’t. “No. I reserve the right to change my mind every five minutes.” He might vote Labour in one election. Lib Dem the next. “I voted Tory once, I think.” Ultimately, he believes that power corrupts. “We’ve had awfully poor leadership of late. Despite the pandemic, which you’d have thought would have brought us closer together, we’ve had even more division.”

The last time Bonneville felt like we were allied, properly, as a set of nations, was that fairy-tale Olympic fortnight, now more than a decade ago. “Those two weeks where we all felt good about being in this country. I think Britain felt truly great and the kingdom properly united, in a way I hadn’t felt in my adult lifetime. Ever since then, there seems to have been this fracturing. God knows we need to find a way of healing.”

He says he’d never bite his tongue. Then, “No, err, hang on, let me be really honest, yes, I do.” He thinks cancel culture is “terrifying” – no, not terrifying, “revolting.” He worries about his words being taken out of context. So he’s increasingly judicious about what comes out of his mouth. But every citizen should be able to express themselves, shouldn’t they? Just because you’re an actor doesn’t mean you’re no longer a citizen, does it? “But because you’re off the telly, there’s a belief among some people that you should shut up.”

Well, Hugh Bonneville has a message for those people. “I think anyone who says ‘stay in your lane’ can just fuck off.”

Playing Under the Piano: From Downton to Darkest Peru is available at amazon.co.uk; The Gold is available to watch on BBC iPlayer

Read more: Bridgerton’s Luke Thompson on privacy and the power of the theatre

The post Hugh Bonneville: “Because you’re off the telly, there’s a belief you should shut up” appeared first on Luxury London.