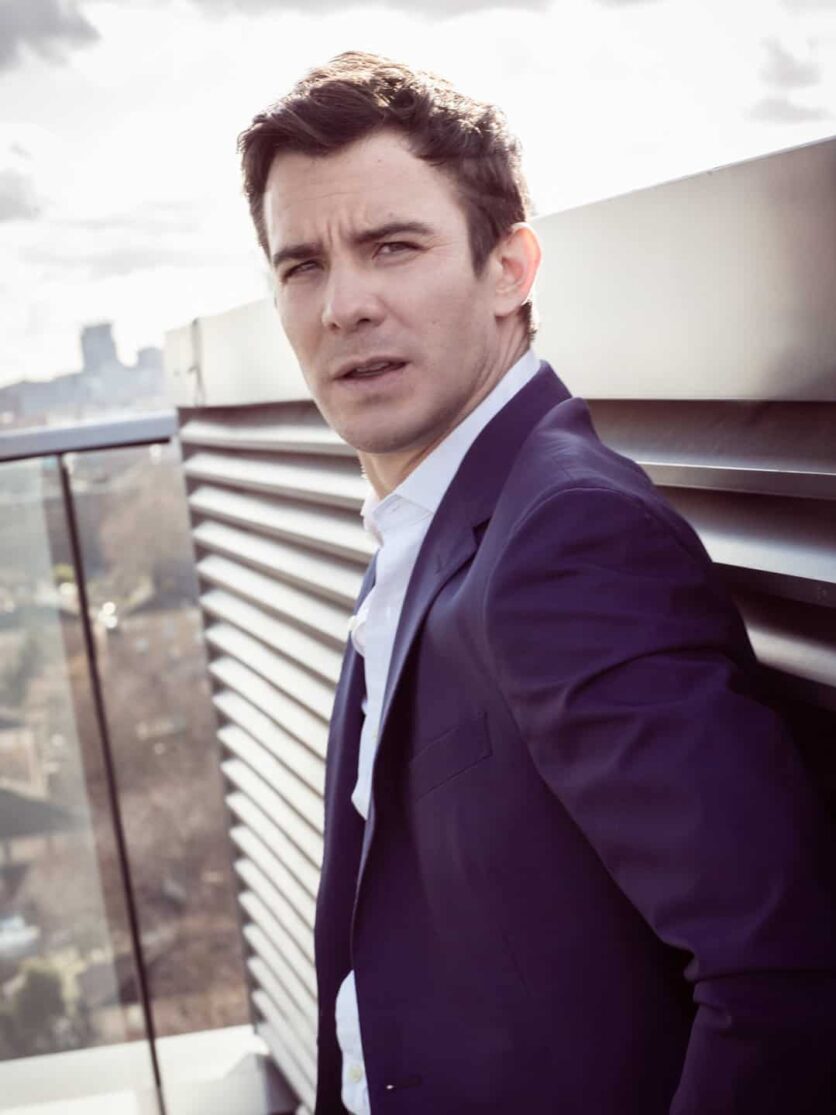

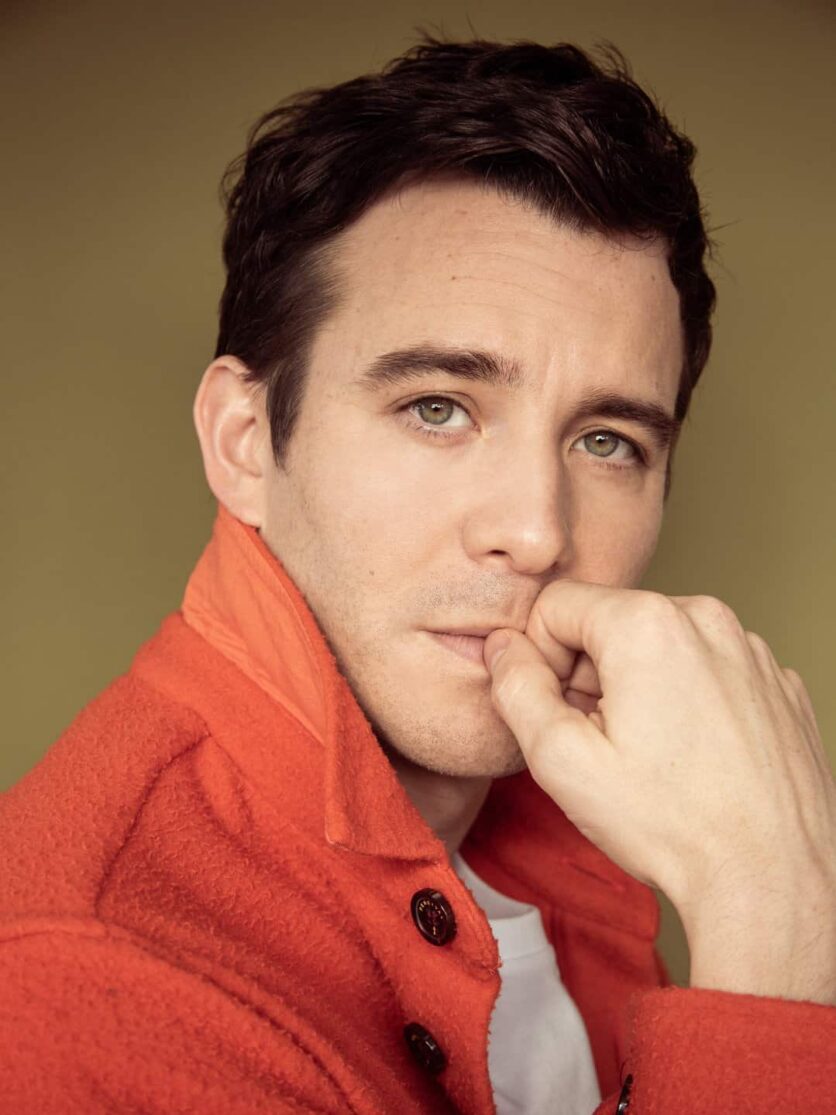

I had one objective when I interviewed Luke Thompson: break him. Find the chink in his armour and pry it open until he spills his deepest, darkest secrets. I’m joking, of course – I’m no Lynn Barber. But Thompson is something of an enigma, and I have my work cut out when it comes to cracking the code.

For one, Thompson doesn’t have social media, so I can’t stalk him before our interview. “I realised I was finding it hard to focus on a book or anything like that,” says the 34-year-old. “And I was like, God, this constant information-sharing is wrecking my ability to concentrate.” Media appearances? Not much there, either. Aside from a couple of online interviews, Thompson isn’t one to bare his soul to the broadsheets.

So I go in blind. We’re on an early morning video call; Thompson appears wearing a striped shirt and thick-rimmed glasses. Your quintessential English gent: dapper and debonair with a Hugh Grant-esque furrow to his brow and very captivating green eyes. Thompson speaks with a slightly plummy, RADA-certified twang. “We’re just finishing up filming,” he tells me.

Filming, that is, for season three of Bridgerton – the most-streamed series on Netflix after Squid Game. Set in Regency London, the programme follows the romantic lives of the titular family. Season one focused on Daphne Bridgerton’s liaison with the marriage-averse Duke of Hastings, while season two traced eldest son Anthony’s quest to find a wife. “I’m extremely proud of the show,” says Thompson. “You’re enabling people to drift away on a bit of romance, you know?”

His character, Benedict Bridgerton, is the second son. With none of his brother’s responsibility, Benedict is free to dabble in the bohemian life – he writes poetry, paints, and engages in trysts with various women. Anthony is all brooding glares and martyred monologues; Benedict is frippery shirts and strategically-fitted breeches. “One of the quotes from the book [it was the novels by Julia Quinn that formed the basis of the television show] is something along the lines of, ‘he wishes he was a little less Bridgerton and a little more himself’,” says Thompson. “I think that drives his whole story. He’s trying to know who he is outside the family.”

Benedict is yet to have his moment in the limelight; the third book is about him, so it was assumed that he would take the mantle for the next Netflix series. Instead, the third brother, Colin, will take the floor. “Because [Benedict] is not front and centre – he’s sort of leaning in the back of the ballroom with a grin on his face, judging people – he’s available a little bit to the audience, but not fully,” Thompson has said.

Sound like someone else we know? Thompson is guarded, albeit good-naturedly, on the more personal stuff – questions that might give me an idea as to who he is after a scene has wrapped. Does he enjoy a night out, or is he more of a takeaway and box-set sort of guy? “To be honest, after rehearsal, I’m comatose most of the time.” No joy there.

Indeed, Thompson won’t even elucidate on his favourite film, claiming not to “have any”, so I should have known that naming the craziest thing he’s ever done would be beyond the pale (“Oh, goodness. Whatever you want it to be. Let your imagination run wild”). I do manage to wheedle out of him that he enjoys French cuisine, but then, he did grow up in France. Good job, Sherlock.

I think I’m beginning to get it, though. For Thompson, it’s all about the art. On the social media thing, it’s not just about a diminishing attention span, it’s about projecting, or not projecting, a certain image: “If you don’t know much about [an actor], you’re more likely to be able to fill them with yourself. The more you give people, the more you’re limiting their ability to imagine you into something else,” he explains. “It’s sort of like those old cameras where, if you opened them at the wrong time, you’d ruin the negative.”

It’s almost like Thompson feels that, if he deigned to reveal his favourite film, or admit that he enjoys a Domino’s pizza once in a while, the spell would be broken and I wouldn’t be able to think of him as a Serious Actor Who Does Shakespeare.

That wasn’t just an analogy – it was Thompson’s love of the bard that got him into acting; his debut performance was as Lysander in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and he has since appeared in productions of Julius Caesar, Hamlet and King Lear. “[TV] is not the same as someone looking at you. It’s sort of like a cubist painting, all taken to pieces and you don’t really get to feel it,” he says. “What I love about theatre is being in the room with people. You can get a bit drunk on an audience.”

“It’s very important not to be too – what’s the word – polite?”

Luke Thompson

Now, after a hiatus in the frothy, bodice-ripping world of Bridgerton, Thompson has a suitably meaty stage role to get stuck into. It’s Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life, which opened in late March at the Harold Pinter Theatre. “I’d read the book, and I knew [director Ivo van Hove’s] work and found it very exciting. So, with the combination of those things, I thought, ‘Wow, this is really special’,” he says.

The 2015 novel follows the lives of four friends in New York: Malcolm, JB, Jude, and Thompson’s character Willem. Jude’s is the central storyline, and it’s not happy, comprising abuse, rape, suicide and self-harm. Happy Valley’s James Norton, who plays the protagonist in A Little Life, has discussed having therapists on hand for the “disturbing” role. It’s going to be intense. Which is exactly what intrigued me – and everyone else fighting for tickets – about this production.

Critics’ reception of the novel was fairly unanimous. Yes, it’s heavy, but Yanagihara averts ‘trauma porn’ territory with remarkable prowess. Will van Hove be so lucky? How does one transpose such subject matters onto the stage without it feeling overblown and dismal?

For Thompson, it’s a moot point – he feels strongly that the content of the play should not be sanitised: “It’s very important not to be too – what’s the word – polite? Yanagihara wanted to write something unignorably visceral, and just hit you in the face with it. That has to translate into the play.”

“Obviously, there’s space for theatre to be somewhere you go and forget your troubles,” Thompson continues. “But I also think we also go there to be upset. The whole exercise is, you know, provocative. It has to be provocative.” Plus, he refuses to see A Little Life as simply ‘sad’. Through the hardship, he says, it is a beautiful character study and depiction of love and friendship. “And, actually, it’s a very relatable story, which I know sounds mad because of the Baroque nature of the suffering,” he continues. “But it’s just about pain and how we nurture our pain because, if we let go of it, we wouldn’t really know who we were anymore.”

Thompson is incredibly articulate when discussing his roles, adopting the tone of an English university professor. Unsurprising, perhaps, for a man whose favourite book – he granted me an answer to that question at least – is Dostoevsky’s philosophical 840-page tome The Brothers Karamazov. When he’s not reading Russian literature, the actor can be found playing the piano, before, presumably, popping off for a bit of escargot and never, ever scrolling memes or watching TikToks.

On paper, it sounds affected. As well as refusing to be drawn on light-hearted inquiry, Thompson won’t take the bait when I probe him on those famous Bridgerton sex scenes, instead launching into a high-minded meditation on the creative power of eroticism (“actually, it’s a piece of physical drama”). When I ask him about the series’ ‘colour blind’ approach (where actors are cast irrespective of their ethnicity or race) he corrects me pointedly: “Colour conscious. Colour blind would mean that [race] is completely disregarded. Genetics exist in this world, it’s just a slightly parallel fantasy.”

But, and I cannot stress this enough, Thompson is not affected. A giddy, slightly boyish sense of humour shines through as he reminisces about filming an episode where Benedict and Colin drink opium tea. “It was a bit gross because it was a dinner scene and, by the end of the day, the food absolutely stank,” he grins. “It was a hot room and, to be honest, I did start to feel a bit high.” He has an easy smile, effortless warmth and, despite clearly doing the press rounds for A Little Life, appears to have time for everyone. “Are you going to come?” he asks, earnestly.

Celebrity certainly hasn’t gone to Thompson’s head. “[Being a public figure] changes a lot of things, but it can also be a choice. You can choose to let it become this watershed thing,” he muses, towards the end of our interview. “I get noticed [in public] occasionally, that’s really nice. I hear about fan accounts, and that’s rather charming. But the main way Bridgerton changed my life, for which I’m extremely grateful, is that it provided me with more hours in front of the camera.”

And that, I think, is what it all boils down to for Thompson. Here is a man who genuinely loves his craft and wants nothing more than the opportunity to hone it.

So, no, I didn’t necessarily peel back the layers of the onion. What I did do was check my own cynicism. Not everyone who’s off social media is doing it to be sanctimonious. When people wax lyrical about their passions, they sometimes mean it. And, in the age of information, it’s nice to have a bit of mystery. “What you hide is just as important as what you reveal,” Thompson has said, and I’m coming around to that mode of thinking. I no longer want to spoil the negative.

‘A Little Life’ runs at the Harold Pinter Theatre from 25 March until 18 June 2023, tickets from £15, haroldpintertheatre.co.uk

Read more: Tahirah Sharif on the BBC and hitting the big time

The post “It has to be provocative”: Bridgerton’s Luke Thompson on privacy and the power of theatre appeared first on Luxury London.