Sixty-two years ago, bookshops across the UK were doing an even brisker trade than usual in the run-up to Christmas. But the rush had nothing to do with festive shopping for family-friendly tomes to distribute to relatives before the turkey was carved. The queues were for Lady Chatterley’s Lover: a book written over three decades previously which would, with sales of two million copies over the coming 12 months, outsell even the Bible.

Even now, the reputation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D.H. Lawrence is still so powerful as to render a clear perspective of the book nigh on impossible. The tale of an upper-middle-class married woman and her torrid affair with gamekeeper Oliver Mellors, partly prompted by her husband Sir Clifford Chatterley being paralysed from the waist down, explores themes of integrity, wholeness, class and the relationship between mind and body.

But it was the language and the sex scenes which resulted in Lawrence, unable to find a publisher who would print it, only ever distributing 1,000 privately-made copies to friends and subscribers in 1928. Contrary to popular belief, the novel isn’t an endless succession of sex scenes. But when they appear, they leave little to the imagination:

And when he came into her, with an intensification of relief and consummation that was pure peace to him, still she was waiting. She felt herself a little left out. And she knew, partly it was her own fault. She willed herself into this separateness. Now perhaps she was condemned to it. She lay still, feeling his motion within her, his deep-sunk intentness, the sudden quiver of him at the springing of his seed, then the slow-subsiding thrust.

A heavily edited version of the book did appear in the UK in 1932 but it wasn’t until 1960, 30 years after Lawrence had died, that Penguin Books found themselves under the scrutiny of the Obscene Publications Act due to the publisher, finally, deciding to print the full, unedited novel.

Rather than suppressing the book for another three decades, it was the implantation of the Obscene Publications Act the previous year that actually prompted Penguin to publish the unedited version. The new law stated that any book considered obscene by some but that could be shown to have “redeeming social merit” might still be lawfully published.

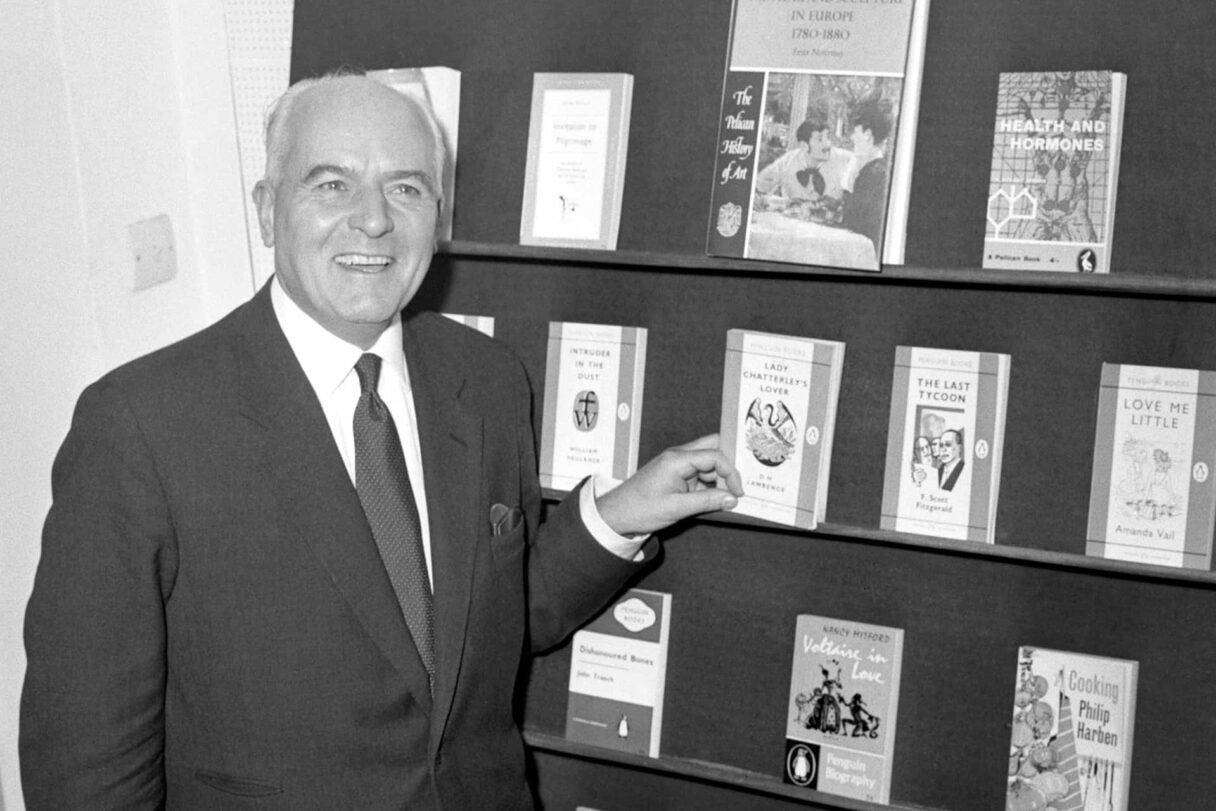

With the unedited version of Lady C, as it had become known, having recently been given the all-clear to be published in the United States, Penguin co-founder Allen Lane saw his chance, publishing the book with the familiar Penguin orange-and-white paperback cover design for just three shillings and sixpence, the same price as a packet of 10 cigarettes.

It was partly the fact that the book was now affordable to people beyond the middle-class literary cognoscenti that prompted the Director of Public Prosecutions to act. Penguin may have felt that the public were finally ready to devour full-strength Lawrence. Prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones felt differently. As the trial began at the Old Bailey on 20 October 1960, he asked the jury: “Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?”

Sir Allen Lane, Chairman of Penguin Books, during a press conference after the court trial, 2 November 1960. Image: Alamy

Griffith-Jones continued by arguing that the novel could “induce lustful thoughts in the minds of those who read it”, and also that it “sets upon a pedestal promiscuous and adulterous intercourse. It commends, and indeed it sets out to commend, sensuality almost as a virtue. It encourages, and indeed even advocates, coarseness and vulgarity of thought and language.”

That vulgarity consisted, according to the prosecution, of 13 sex scenes and 66 swear words, from ‘balls’ and ‘arse’ to much stronger expletives which, even today, can’t be published on websites like the one you’re reading. Not only that, but Griffith-Jones even took issue with words like ‘bowels’ and ‘womb’ which appeared in the prose.

Mollie Panter-Downes was a journalist reporting on the trial for The New Yorker magazine. With laconic importunity, she described the bizarre spectacle that was unfolding in Court Number One.

“Practically every description of lovemaking in the book must have been read out by Mr. Griffith-Jones, with awful emphasis and the air of imparting some reprehensible rite that would be news to all his listeners, and it was interesting how well the writing stood up to the treatment.”

Sexual intercourse began in nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me).

Between the end of the Chatterley ban.

And the Beatles’ first LP.Annus Mirabilis, Philip Larkin

The defence was well prepared when the time came. Leading counsel for the defence Gerald Gardiner stated that Lawrence was regarded by some as the greatest English writer since Thomas Hardy. He spoke of Penguin’s high reputation as a publishing house but most importantly, he instructed the jury that what they must ask themselves was one of the test questions of the new Obscene Publications Act: was it likely to corrupt or deprave the weak?

Members of the jury were then given a few days to read the book themselves. Barred from taking their copies home, they were made to read it in the jurors’ room before, over the course of three solid days, 35 different professors of literature, authors, publishers and four Anglican churchmen took the stand to testify to Lady C being a work of high literary merit.

These included E.M. Forster (a friend of Lawrence) who stated that he put his late fellow novelist “enormously high” in the “great puritan stream” of English writers. While Dr John Arthur Thomas Robinson, Bishop of Woolwich, stated that Lawrence was trying to portray sex as something sacred, in the real sense of an act “almost of holy communion.”

By the time the defence rested, it seemed that the jury would be able to complete a PhD in Lawrence Studies. Some witnesses noted that some of the dozen men and women in the jury box visibly wilted as the hours of protracted academic debate between Griffith-Jones and the learned array of Lady C devotees on the scatological and thematic significances of the novel were dissected, scene by scene, swear word by swear word.

Lawrence once spoke of Lady C as being a ‘little boat’ that he was “determined to stand by… and to send her out into the world as far as possible.” Posthumously, he was to have his wish granted. It took the jury just three hours to bring in the verdict to Mr. Justice Byrne of not guilty.

A delivery driver for Penguin Books delivers copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, 2 November 1960. Image: Alamy

London’s largest bookstore at the time, W&G Foyle Ltd, told the BBC its 300 copies were sold in just 15 minutes and it had taken orders for 3,000 more copies on the release date of 10 November – just a week after the verdict was reached. 400 people were in the queue waiting for the shop to open. Hatchards in Piccadilly sold out in 40 minutes.

Selfridges sold 250 copies in the first few minutes with a spokesman for the department store stating: “It’s bedlam here. We could have sold 10,000 copies if we had had them.” The book continues to sell, partly in thanks to numerous TV and movie adaptations over the past 60 years. Yet there was one copy of Lawrence’s ‘little bird’ that recently had its wings clipped.

In 2019, arts minister Michael Ellis put a temporary export ban on the actual copy of Lady C used by Justice Byrne at the 1960 trial. With many passages underlined by the judge’s wife, Dorothy, so he “would know where the dirty bits were”, the book had been sold at Sotheby’s in London for £56,250 to an unnamed American buyer along with the damask bag that Lady Byrne made to ensure that her husband could carry the book discreetly around the Old Bailey.

Sir Hayden Phillips, chairman of the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest, said, “The prosecution of Penguin Books for publishing Lady Chatterley’s Lover was one of the most important criminal trials of the 20th century. Judge Byrne’s copy of the novel may be the last surviving contemporary ‘witness’ who took part in the proceedings.”

The export ban was upheld and, thanks in part to a crowdfunding campaign, the book now belongs to Bristol University. With some of the pages coming loose and a rust mark left by a paper clip on the cover, it’s far from the most pristine copy of Lawrence’s novel. But it’s a small, yet vital, remnant nonetheless of a trial that brought sex, swagger and the Swinging Sixties a small step closer to reality.

The new adaptation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover debuts in cinemas on 25 November 2022 and on Netflix on 2 December 2022.

Read more: The true story of Marilyn and the Kennedy brothers

The post Lady Chatterley’s Lover: The banned book that kick-started the Swinging Sixties appeared first on Luxury London.